Learning While We Can

How often are we prone to visiting a location and simply letting the familiar slide by us? How frequently do we look closely at those things whose shapes, sounds, and subtleties are often lost in the vibrancy of a bright Saturday afternoon?

When we stop to think about those places we’ve been, the all-too-familiar strain of “familiarity breeds contempt” rings true in our minds, for we often, like it or not, fail to understand the significance of what we encounter. It’s to this moment, or collection of moments, that I’m going to petition your attention today.

I’ve been to Galway a handful of times, each with varying degrees of purpose and intent. A few times have been under the auspices of meeting people, a few more due to work obligations, and still more “just because.” In each case, the storefronts always appear the same, the parking structures are the same irritating conjunction of steel and concrete, and the food is always incredible. Yet, for each journey, there’s still something missing, some slice of provenance or purpose that seems to nag at the corner of my mind.

There’s colour to be found everywhere. From the streetside markets with vendors hawking their goods, the smell of cooking oil starkly contrasts with the yeast and sugar of freshly made doughnuts to the vegetables and meat sold in their riotous displays of garden, sea, and field. It’s rarely subtle, for how could you miss the cacophony of people in harried lines, mouths watering for the next bite of heaven?

But these moments aren’t commonplace. They are the storefronts that line the stone walkways, the rushing waters under the bridges, and the gentle thrum of the masses as they make their way through alleyways, sidewalks, and promenades, heads pivoting on necks as they crane to see all the “new” amongst the sea of history and the familiar.

The rusted structure you see at the top is something we’d usually pass by. A fountain, constructed in 1984 to celebrate the 500th anniversary of Galway City’s incorporation, lies on a bed of concrete, its hulk of rusted steel a homage to the Galway Hookers and their sails stained with animal blood and ochre. It’s present but passable in a way that, as noted previously, breeds a certain contempt for its existence. It provides a stark offset against the lighter greys and greens of the Eyre Square (aka the John F. Kennedy Memorial Park, natch) but is completely invisible if you’ve been there before.

I draw your attention to this because, in these times, our inability to understand these bits and pieces of culture, strewn about as they are, in the public squares of our journeying tells us more about the condition of our social understanding than anything else.

We are bedazzled by the consumerism and fantasy of a world changed by the daring-do of oligarchs and politicians rather than the subtle shades of rust-coloured history lying at our feet. We opt for the High Street when the public square contains the foment of centuries’ wisdom wrapped in the guise of blood-stained sails from our ancestor’s toil. However contemporarily interpreted, the symbols of our past should be a lighthouse to guide us to understand more about our place in time.

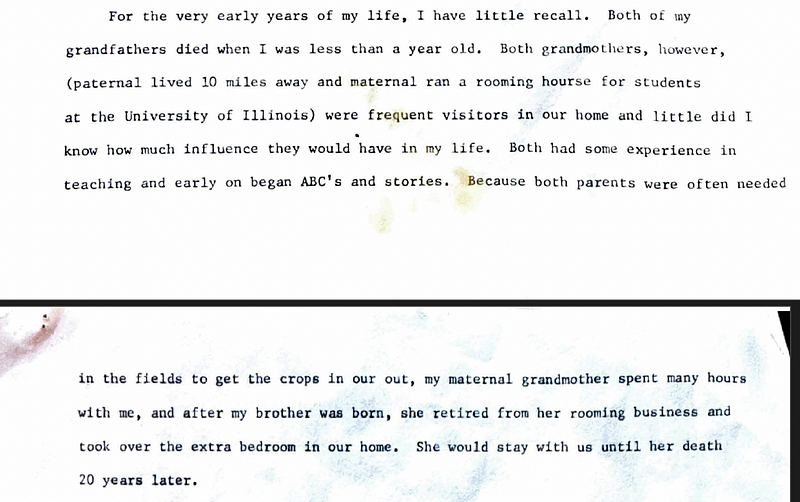

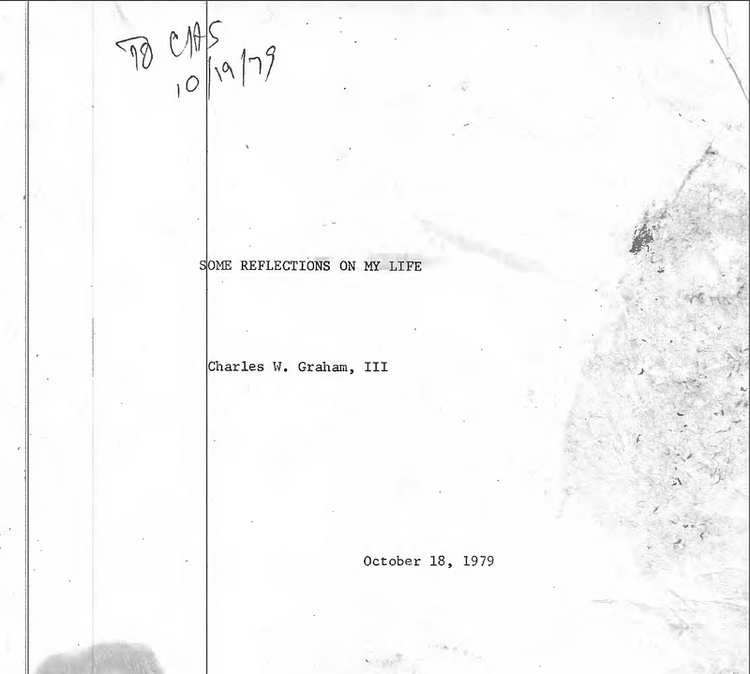

We may not have the benefit of sculpture, of a public square nestled in the airy confines of a seaside city such as Galway. We may be landlocked and snowed in, the verges of spring barely touching our waiting hands and hearts. And yet, even in these in-between times, we can pause, appreciate, and learn from the artefacts of generations past through the portals we hold in our hands and sit at our desks. We can dig deep into the bloodied history of war, politics, religion, and our implicit biases towards those who don’t look like us. Through art, music, and written words, we can seek to understand the cries of the marginalised and oppressed, the histories not written by the victors but by those who were left behind. We can revisit, however painfully, the learnings of philosophers and politicians, each who strove to relay the importance of an inclination towards the “we” and not the self-serving egoism of modernity.

However you choose to go about it, understand the gift of these ordinary devices in the world around you. They may not be fanciful sculptures, but the power of words in a book hits just the same. They may not be plaques on the sides of buildings, but the protest songs of a century ago are still resonant today. Photography can unlock memories and meaningfulness; an artist’s canvas is the same. These are the artefacts of our time, public square, and daily lives. We’d do well to learn what we can while we may.

May it ever be so.