Into the Sacred and Profane

There’s a delicious irony to the fact that La Sagrada Família is both a church and one of the most visited landmarks in Barcelona. The appeal of a church that has endured construction for over a century draws visitors from around the globe and is nothing short of a miracle. All races, creeds, religions, genders, and whatnot are represented, milling about the stone floors with a reflective stare at Gaudí’s vision of what a church should be. I wonder how many of these people check their beliefs at the door and engage with their surroundings in the reverence that was intended versus the drive-by curiosity of a tourist. Something to consider, I suppose.

La Sagrada Família is a collision of the mystical and the mundane, the fanciful and the banal, the fever dreams of an artist and the careful calculation of a physicist and architect. It is a delightfully chaotic whole nestled in the ordinary structure environment of the Gothic Quarter in Barcelona, an island unto itself, beggaring belief. This chaos is designed, in my opinion, to lead to the inevitable reflection of our humanity, those intrinsic thoughts, feelings, emotions, and physicalities that comprise our bodies and souls. Embodied in stone, we find ourselves in the most holy of holies, gently led to our communion and worship table.

This guidance starts from the moment you look at it, whether up close or from afar, like yesterday’s story around Parc Güell. La Sagrada leads your eyes to the heavens, representing the saints, apostles, and the Holy Family as an ascension through our histories. It’s a monument to teleology, a designed experience to lead to a belief, a reflection of the holy as much as the profane.

Perhaps unintentionally, in relation to St. Peter’s Basilica, St. Paul’s Cathedral and other churches of Christendom, La Sagrada has an element of humanity profaning its presence. The cranes are looming large over the outside towers, the contrasting stones emplaced over decades of ongoing construction show unequal wear patterns, and the wire and steel fencing surrounding each side. Stepping through metal detectors is perhaps the penultimate offender, acknowledging that we cannot be trusted to preserve and protect what is culturally significant to a people and place.

The profane is necessary, at times, to complete a vision. The idea that a church would be pure, separated from the masses that comprise its congregation, and absolved from the pollution of sin is a story for another time. Wars have been launched, ostensibly under the banner of holy retribution, that has seen the plundering of compassion and kindness for the sake of the papal coffers. No, I’m talking much more directly about the idea that La Sagrada embodies the very nature of who we are in its profanity. It embodies our temptations, lusts, and desires. It grabs ahold of our heads and hearts, demanding obeisance to the magnificence of its sculpted towers and windows to draw us into the quiet heart of it all inside. The riotousness of its exterior belies the sanctuary of its soul.

It’s not perfect, nor do I feel that Gaudí would pretend it should be if he were alive today. It’s a testament to the jagged edges of who we are, the juxtapositions of good and evil, light and dark, angels and demons who comprise our world, spiritual or otherwise. Here, I believe that Gaudí’s vision is most realised and tangible.

You enter and are reminded of the garden, the fall of humanity from being embraced by a God to being separated, achingly so, by free will. The fact that theological scholars have debated this genesis over the centuries and ecumenical wars fought over this gnosis is casually discarded here at the entrance to your journey. La Sagrada casts a name and angels at your horizon and beckons you into the garden of our beginning.

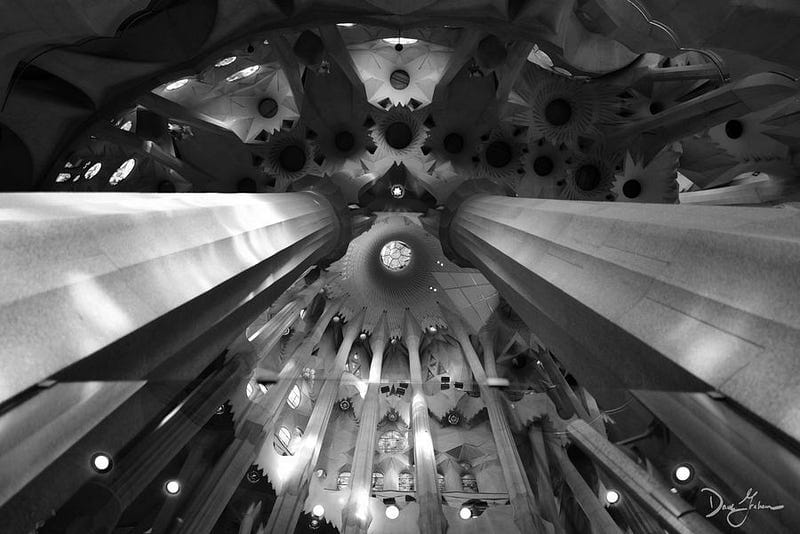

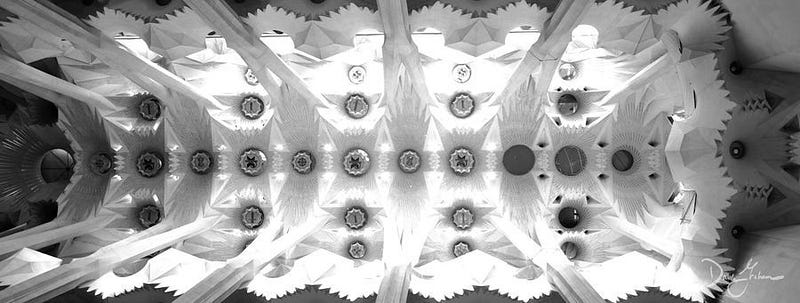

When you remove the spectacle of people crowding the floor and the pews lined up before the altar, La Sagrada is awash in light. It filters between the columns, reflected off the smooth marble of the floors and ceiling, stained glass shattering the purity of brightness into a mosaic of tesserae colours. It hits you like a cold pail of water to the face, awakening that primal understanding that when God separated light from dark, the heavens above from the firmament below, this must’ve been how it was. Light becomes spirit, spirit becomes awareness, and awareness becomes awe. It captures your breath, and you’re lifted from the ordinary into the confines of the arcing vaults above. Here is where the profane finds its rest and is burned away.

Pictures cannot, nor will they ever be able to, do justice to the moment you first look at the ceiling. Everything you’ve experienced of neo-Gothic, classical, or medieval architecture is simply dull by comparison. Michaelangelo’s paintings on the ceiling of St. Peter’s may be enshrined forever as the highest of art, but they hold narry a candle to Gaudí’s worship of the infinite. Every cut, every curve, every trace of angel’s wings on Catalan sandstone and granite has purpose and intention. It draws your eyes to the heavens, these portals of light that remove all trace and awareness of darkness. I’d suggest that darkness in La Sagrada is more an ideology than a manifestation because there is no place for it to run. Even the shadows are bright with expectation and hope.

This is where most people dwell, bathing in the radiance of natural light, broken into a million shards of chaotic colour. There’s the murmur of a thousand voices, all telling their stories to friends, family, and loved ones in person or across the cellular expanse of technology. It’s where you sense that humanity is the most vulnerable: under the aegis of majesty, we’re all stripped of pretence and posturing. We become unmade from all we carried through the front door: bare, naked, and unshamed for it.

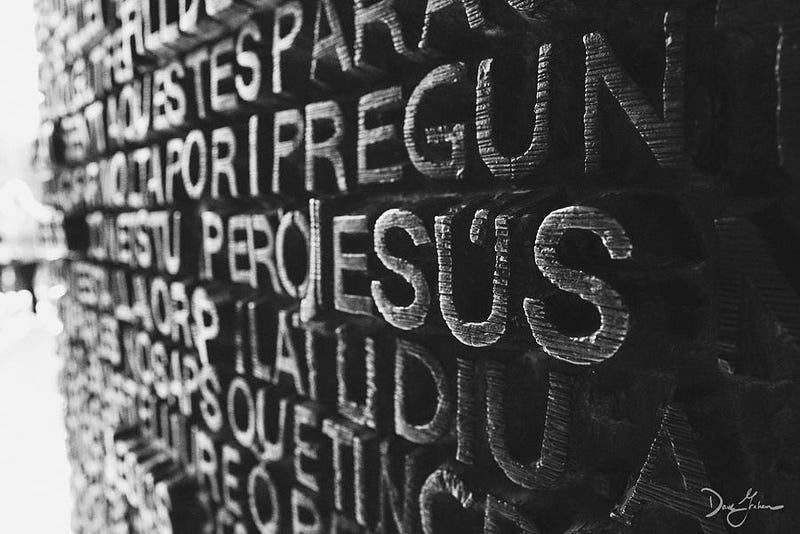

Here, we finally find our escape into the harsh realities of a world mired in conflict. We’re provided an exit through doors poured into words of meaning, verses and questions regarding the trials and tribulations of the man we called “Jesús,” the Christ. We are brought to the pillory of Christ’s beautification, the breaking of his body from the spirit within, a reminder of how even the most lowly amongst us can be driven yet further into the ground. We face the absence of beauty and the reality of our innate cruelty and inhumanity. We are, after all, fallen from the garden of our Eden to the depths of depravity. Gaudí’s vision again captures our profane natures in the arms that encircle this stone.

This is La Sagrada Família. This is a stone and flesh testament to who and what we are. It’s an embodiment, perhaps in ways never intended, of what a sacred family is: our communities, our cultures, our people, our provenance. It’s a journey of cognisance from our creation to our destruction and the communion we have at all stations along the way.

La Sagrada Família lives and breathes within us as much as it stands tall and proud over the Barcelona skyline. It’s achingly beautiful in its incomplete state. Perhaps this is a reminder to all of us that we’re never quite complete, even in all of our established ways and means. Maybe it’s a signpost to point us to something more significant than the flesh and bones we possess. Perhaps it was never meant to be finished, despite Gaudí’s hopes and dreams, and it stands as a testament to our unfinished work here on this earth. I only have conjecture as to its ultimate meaning for our stories.

But, beyond all of this, I know I’m more whole every day. I take comfort in walking through those wrought metal doors and exiting the same, and I can say I’m one day closer to being what I am supposed to be and one day removed from what I’m not. I’m joyful at the opportunity to understand, in no small part, that I can be both broken and holy, angel and demon, light and dark and that this is all ok.

Maybe this is a bit much for a Tuesday, but c’est la vie. We all have our La Sagrada moments of awe and inspiration, so embrace them as you happen upon them, for they’re made to enlighten your soul.

May it ever be so.