A Beginning, Part 2: The Early Years

I step back into my father’s story with very little preamble, starting with his early childhood. As you may recall, he was born in the small farming town of Galesburg, Illinois, a scant 45 miles or so from the Mississippi River that cuts through the bluffs and rich soil of Iowa and Illinois. This was a formative experience as you will no doubt see.

Charles’ Story:

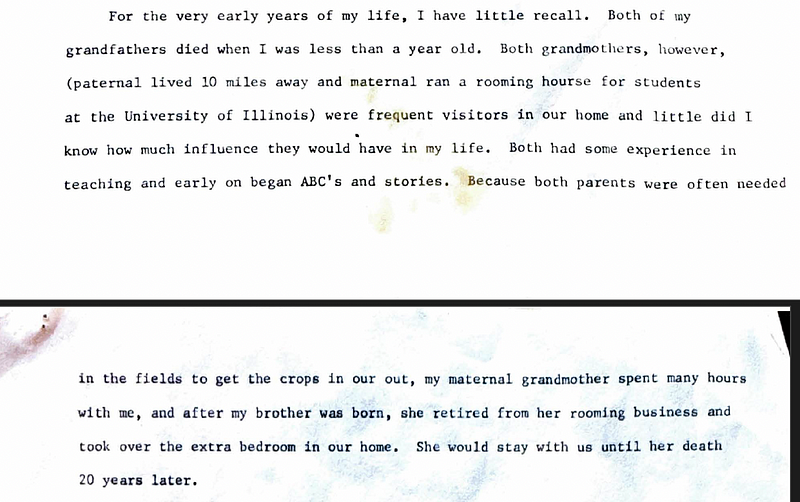

For the very early years of my life, I have little recall. Both of my grandfathers died when I was less than a year old. Both grandmothers, however, (paternal lived 10 miles away and maternal ran a rooming house for students at the University of Illinois) were frequent visitors in our home and little did Iknow how much influence they would have in my life. Both had some experience in teaching and early on began ABC’s and stories. Because both parents were often needed in the fields to get the crops in our [sic] out, my maternal grandmother spent many hours with me, and after my brother was born, she retired from her rooming business and took over the extra bedroom in our home. She would stay with us until her death 20 years later.

My Explanation:

I find my father’s impressions of his early childhood interesting on a number of fronts. From my own personal experience, my father modeled much of the same behaviours as his grandmothers, spending time at the dinner table teach diction and spelling, ensuring that many of the nuances of the English language (pronounced with a particularly chewy tone) were expressed properly. In stark contrast, however, my father was not given over to the residence of family members in his own abode. Given his approach was to “get the crops in [and] out” by working long shifts at the local hospital, I suppose you could find a sympathetic understanding of this nouveau take on homesteading and education. I can tell you that my father's absence on many occasions led my mother to take a more important role in my development than him. And this, perhaps in an uncanny collision of kismet and circumstance, was mirrored in my father’s life as well.

Charles’ Story, Continued:

When I was 4, we moved into a monsterous [sic] old Victorian farmhouse on the land where my paternal grandmother lived (she took up residence in the tenant house 1/4 mile away) and dad expanded his farming enterprises. This house, which I know my mother disliked intensely (and still does), is the “home” I will always remember. It served as the summer centeral [sic] gathering point for all the relatives and clan. It was not uncommon to have 12–14 cousins, Aunts, and Uncles seated around our table which was overflowing with fresh garden produce or canned goodies from the past. Jokes and stories were freely passed around and we cousins would extole the virtues of California versus Illinois and play monopoly, or explore farm machinery. These were good times.

My Explanation:

It’s fascinating to replay my father’s history through the lense of my upbringing and adult reasoning. The father I knew was almost a loner, having chosen quite deliberately to limit his relationships to a smaller bubble. This remained a mystery to me growing up as I never saw my parents truly engaging with anyone in a larger sense of community except when I was little, and then, only with small groups from their church or my mother’s bible study fellowship. As I grew into my teen years, these relationships seemed to disappear entirely, replaced by more nuclear trips to the farm in Galesburg, my maternal grandparents in Wheaton, Illinois, and other places of historical or phenomenological interest. It was only after his death that I perhaps got a glimmer that there was a locus of responsibility or “care” for folks outside our tiny, little bubble.

Some of the other interesting, albeit rudimentary, tidbits found in this page of text are the emphasis on the Victorian farmhouse and the idea that these days were “good times.”

The Victorian farmhouse perhaps should have a whole chapter devoted to itself, albeit sans pictures since I don’t have any at my ready disposal, and it is, sadly, no longer in existence. After my paternal grandmother passed away, it was razed, and its footprint on several acres was consumed by crops to further enhance yields. What I do remember and can convey at this moment is the grandiose staircase at the front of the house, opposite where we entered (the “back door” as it were) and its glossy, smooth texture of solid wood, creaking treads, and winding escarpment.

As far as the “good times” statement goes, my father never struck me as a particularly emotive individual, having more of a staid or stoic personality that lent itself well to teaching and much less to emotional encouragement. I got snapshots of the underlying personality he seemed to possess in this biography from quiet moments at night during bedtime, unguarded moments on family trips, and rare occasions where his patriarchal armour seemed to drop from the weight of the world. But most of the time, it was flattened, muted by the world around. It took years to unlearn this part of his inadvertent tutelage, and I still have to semi-actively guard against it to this day.

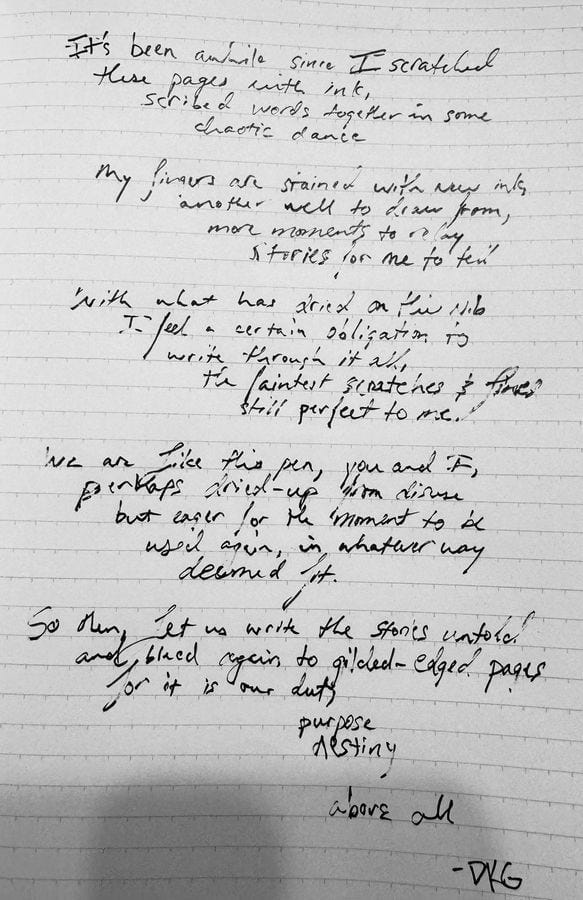

The stories of our lives inform who we are but do not consume the whole. You learn where convergence and divergence matter, where the intricacies of emotions, tears, laughter, and joy drive meaningfulness into the almost grey fields of memory. In these snapshots, the veil is torn, and what we believe to be true in most parts is often shown to be nuanced, shattered prisms of a pretence we thought foundational to who we are.

I’m grateful for the words and history as much as for the chance to diverge from the path that perhaps was plotted out for me before I knew it to be so. Maybe, just maybe, my own children will have the same thoughts and understanding, but that’s their story and their time to process.

May it ever be so.