A Beginning, Part 1: My Father

Adoption

A Beginning, Part 1: My Father

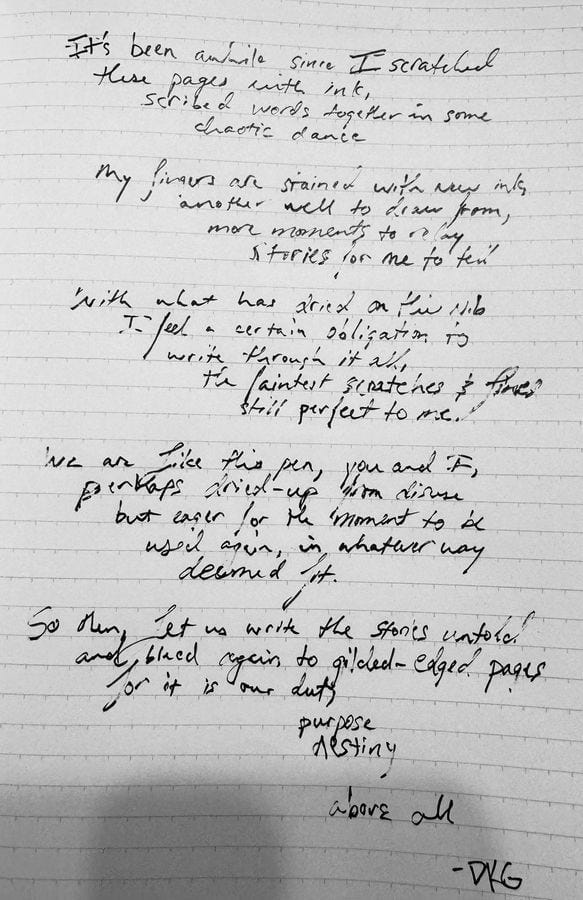

I’ll note that what you’ll see from me over the next several weeks will be a living history. These words will be taken from various bits and pieces of the narrative that form the circumstances around my adoption, and, as such, there’s a certain “liberty” taken in some of the phrasing, etc., that is being used. All of these sources were or are still alive, and where noted, I’ll provide my own set of commentary and storytelling.

I’m aware that adoption (and especially the history of what and who we were before and after it) can be a particularly sensitive topic for people. But there’s a poetic beauty to being brought into the world, given away, and accepted by another family.

There are obviously large variations to this story, both in circumstance and outcome, and I cannot emphasize enough that many of these systems were unequivocally maintained and sponsored through an oppressive religious campaign that stripped young women of all creeds, colours, religions, and identities of their sacred bodily autonomy and rights. What has been done in the name of “God” has been atrocious and unconscionable, and we will spend generations unwinding, apologizing, and repairing the damage that has been done.

I hope that through this one lens I provide, this narrow, winding staircase I’ve climbed up and down over the years, you’ll be afforded a story of hope, of naked honesty, and perhaps a new understanding of what adoption is and what it means.

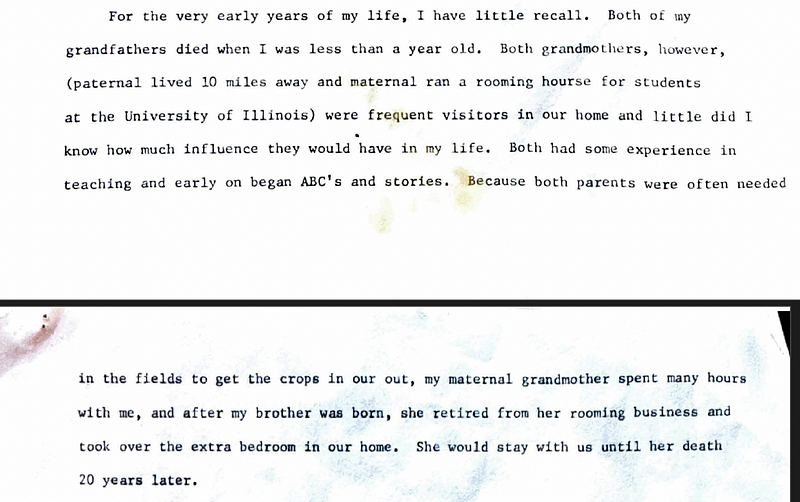

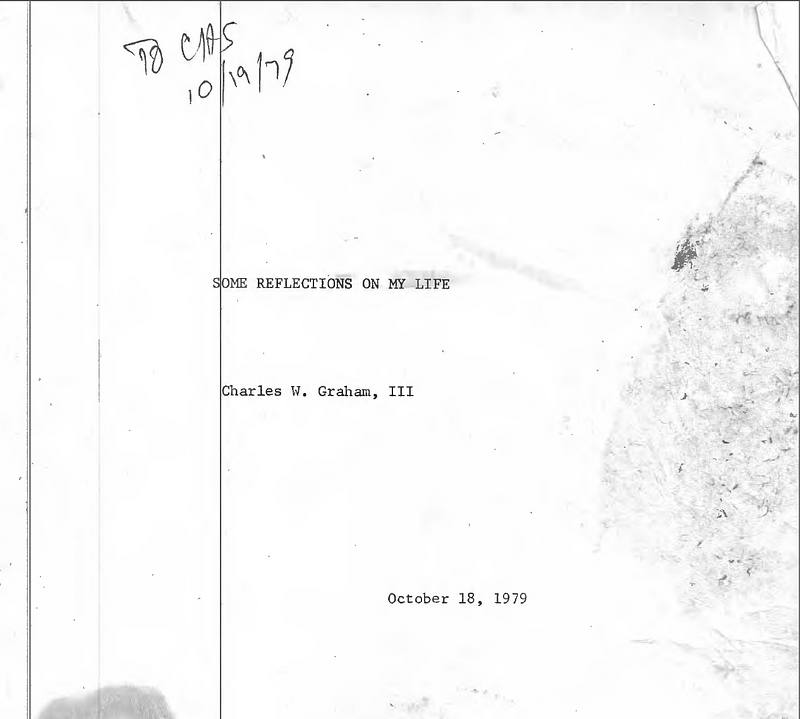

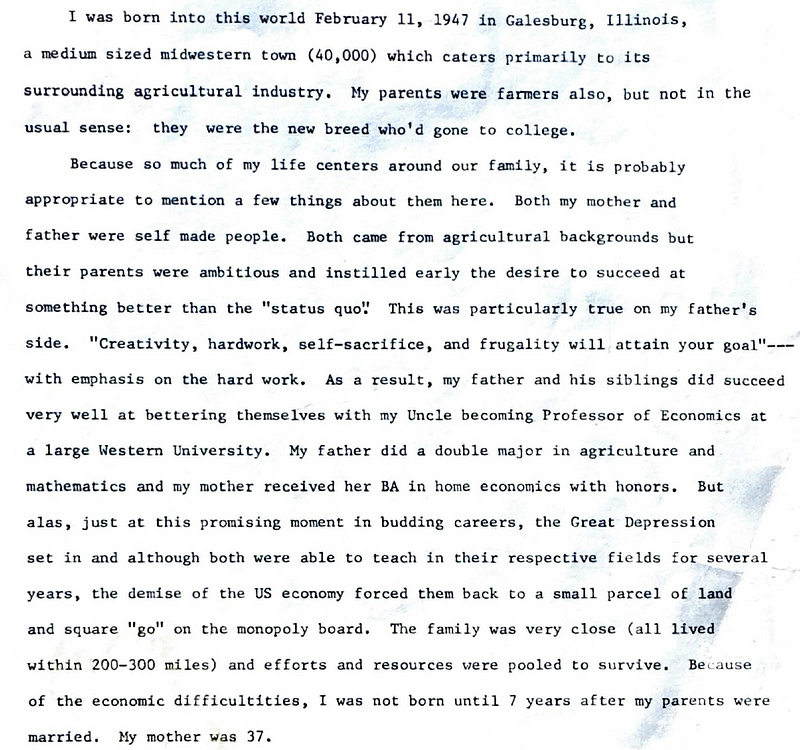

My story begins with my deceased father’s autobiography, provided to the adoption agency that wanted to have a particular understanding of my parents and their ontological reasons for adoption. For each page of his story, I’ll provide the raw capture of the page, a transcription, and a little bit of how I understand the background to play out.

Charles’ story:

I was born into this world February 11, 1947 in Galesburg, Illinois, a medium sized midwestern town (40,000) which caters primarily to its surrounding agricultural industry. My parents were farmers also, but not in the usual sense: they were the new breed who’d gone to college.

Because so much of my life centers around our family, it is probably appropriate to mention a few things about them here. Both my mother and father were self made people. Both came from agricultural backgrounds but their parents were ambitious and instilled early the desire to succeed at something better than the “status quo.’’ This was particularly true on my father’s side. “Creativity, hard work, self-sacrifice, and frugality will attain your goal” — with emphasis on the hard work. As a result, my father and his siblings did succeed very well at bettering themselves with my Uncle becoming Professor of Economics at a large Western University. My father did a double major in agriculture and mathematics and my mother received her BA in home economics with honors. But alas, just at this promising moment in budding careers, the Great Depression set in and although both were able to teach in their respective fields for several years, the demise of the US economy forced them back to a small parcel of land and square “go” on the monopoly board. The family was very close (all lived within 200–300 miles) and efforts and resources were pooled to survive. Because of the economic difficulties, I was not born until 7 years after my parents were married, My mother was 37.

My Explanation:

This story was demanded by the adoption agency as part of their background in understanding the reasons, rationale, and ontology for wanting to adopt a child. This particular agency was very much interested in the religious upbringing of the prospective parents as it was of interest to their “clientele.”

My father, a particularly typical progeny of Midwestern farmer stock, was someone who prided themselves on their education and story, and, as seen in the writing above, he wasn’t half bad. I trace many of my formative writing skills to his efforts and energy.

Also true of my father is the post-Depression environment that he was raised in. In my early childhood visits to the farm where he was raised, the general atmosphere was paucity and restraint, a subtle threadbare theme to the Victorian-style farmhouse and land where his formative years took place. His parents imparted quiet desperation to his future pursuits of monetary gain, and I believe it all stemmed from their education and survival during this time.

It’s interesting to note a few aspects that he called out: “The family was very close (within 200–300 miles)” and “Creativity, hard work, self-sacrifice, and frugality will attain your goal.” The former ended up being something intrinsic to my understanding of family. I’ve lived thousands of miles away from my nuclear family for decades now and found very little reason to ever maintain closer proximity.

This isn’t something I view as a negative characteristic, though, juxtaposed to my wife’s idea of family, it’s sometimes viewed as such. Farm communities naturally had distances built between the homesteads but the idea that family would exist farther beyond the reaches of the “next town over” seemed strangely foreign in that time period.

The latter statement became an ethos I understood from an early age, albeit that “self-sacrifice” became something my mother adopted based on my father’s domination of the household. I can vividly remember my father being gone for much of a given week, working long hours at the local hospital and, while I’m sure he’d note this as “hard work” and “self-sacrifice,” the net result ended up being “absenteeism” and “self-conceit.”

Ah, how the little nuggets of wisdom that we hope to incorporate into our lives sometimes become boulders of insurmountable size.

Reliving someone else’s story, especially after they’ve passed, is sometimes a work of many different threads pulled from your experiences. I know that, deep within the words and paragraphs of my father’s explanations, there lies an ember of a man who did want to be a father, did want to pass along positive traits, and did actually give a damn about what he was a part of.

In the shadow cast by his life, I can reflect on the good as much as the bad of this man who, for better or worse, afforded me the opportunity to be who I am today.

I hope that in this series of retellings, you find yourself revisiting the stories that have made you who you are, that have brought life and loss in the same way that each of us is bound to experience across our blips of cosmic existence.

May it ever be so.

Thank you for reading adoptēre, a publication to uplift and elevate the voices of adoptees and to audit the narrative of the institution of adoption. If you are an adoptee and interested in writing for adoptēre, click here to submit our writer’s interest form and we’ll get you added and published ASAP.

To learn more about the work of adoptēre, click here.